Introduction

Authors of fiction, especially those of the science fiction

and fantasy genres, create immense worlds within their stories. They use a wide

assortment of tools to build rich histories, deep cultures, and lore that

extends far beyond the written words of their texts. One such tool that these

authors frequently employ is the creation of fictional languages. Whether by

modifying existing, real-world languages or by creating their own systems from

scratch, designing a language allows an author to craft a deep font of mythos and

culture from which readers can draw to their hearts’ content. Here I will be analyzing

several devices employed by the creators of three such languages: J.R.R.

Tolkien’s Tengwar Elvish, Doctor Who’s

Circular Gallifreyan, and The Elder Scrolls’

Daedric. Finally, I will provide recommendations for authors attempting

to craft a language of their own.

Please note that I will not be analyzing the translations of

these languages, only the physical appearance and rules for writing the script.

A Brief History

Before

delving too far into analyzing each of these languages, I wish to provide some

background information and context for them. Oftentimes knowing how a script

originated and how it is used can be key in determining its efficacy as a language.

J.R.R. Tolkien's Tengwar Elvish

Tengwar’s

first published appearance was in 1937 in Tolkien’s The Lonely Mountain Jar Inscription. Several of Tolkien’s other

scripts from the 1910s and 20s, such as Sarati and Valmaric, anticipated

features of Tengwar, indicating that the language had precursors and is the

result of several stages of evolution before the final version appeared in The Lord of the Rings in 1955. Most

prominently, the One Ring of Sauron bears an inscription in the Black Speech of

Mordor. Tengwar has several modes, representing different dialects of Elvish.

Here I will focus on two of these modes: the Quenya, or High-Elven, and the

Sindarin, or Gray Elven.

|

| One Ring to rule them all, One Ring to find them, One Ring to bring them all, and in the darkness bind them |

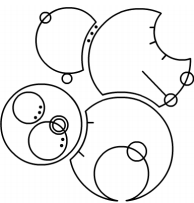

Doctor Who's Circular Gallifreyan

The BBC

television serial Doctor Who

documents the adventures of a time traveler known only as The Doctor, the last

living Time Lord of Gallifrey and sole survivor of the Last Great Time War. The

Time Lords were, as the name implies, the custodians of the flow of time. Their

language is as nonlinear as the nature of time, and consists of nested and

interlocking circles. The screenshot below depicts a message on the console of the Doctor’s TARDIS. While the actual

translations of the language are not known, over the last decade or so the

show’s immense fanbase has compiled the available information about Circular

Gallifreyan to make an unofficial, yet widely accepted, system for

transliterating English.

The Elder Scrolls' Daedric Alphabet

The Daedric alphabet first

appeared in the 1997 video game An Elder

Scrolls Legend: Battlespire, where it was used to write English words. In

the game, the celestial academy of Battlespire was overrun by Daedra, a

capricious class of divine beings. The script next appeared in the 2002 game The Elder Scrolls III: Morrowind, where

it was no longer exclusively used by the Daedra, but also by the Dark Elves of

the titular Morrowind region. Further Elder

Scrolls games continue to use the Daedric script, and in all instances it

has been strongly affiliated with magicka. Items engraved with Daedric sigils

confer effects onto the player, such as the ‘Gray Cowl of Nocturnal,’ whose

inscription reads ‘Shadow Hide (Y)ou’. Predictably, the wearer gets a large

Stealth bonus, as shadows are the domain of the Daedric Prince Nocturnal.

Criteria for Analysis

The

primary criteria I will be using to analyze these scripts will consist of:

usage of diacritical marks, complexity of characters, and overall conveyance.

Firstly, diacritical marks exist in a great number of real-world language

systems, and are used extensively to alter the reading of a character or group

of characters. The simplest Latinate diacritics include the accents acute

(á), grave (à), and circumflex (â)

accents, as well as diaeresis (ä), breve (ă), and macron (ā),each of which

slightly changes the pronunciation of the letter. For fictional language

systems, diacritical marks can lend a great deal of complexity and depth, and

yet provide a way to make reading easier by allowing for explicit pronunciation

guides.

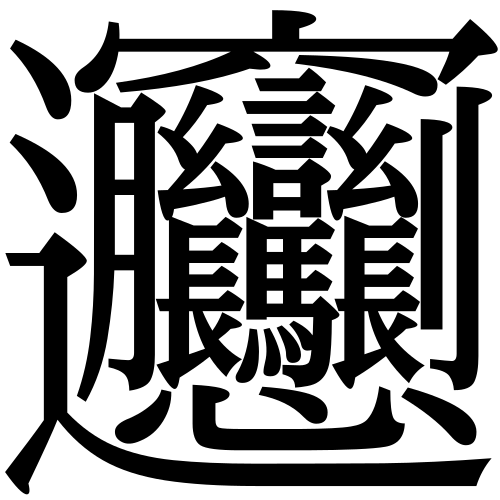

Secondly, complexity of characters can be a good indicator

of how accessible a language is. For example, the Chinese character for a type

of noodle called Biángbiáng consists of 58 individual

strokes and is one of the most complex characters in contemporary usage. This

is an extreme example in a real-world language, yet it shows there are

reasonable limits we must place in order to make a script easily to read and

write. Another facet of character complexity is similarity of glyphs. If

multiple glyphs have a similar root shape, such as our letters ‘d’, ‘p’, ‘b’,

and ‘q’, which are simply inversions of each other, then a reader may find a

script easier to learn and write, as there are fewer distinct glyphs to use. On

the other hand, it is possible that similar glyphs will be confused, so a bit

of discretion is required in saying whether or not similarity is good for a

given script.

Lastly, any language system must make its words

understandable; otherwise it serves very little purpose. Conveyance is the

manner in which a script delivers its meaning. Conveyance can include anything

from direction of writing, shape of the characters, and even the general ‘feel’

of a script. For instance, the Korean Hangul alphabet was created by Sejong the

Great in 1444 for the purpose of making the Korean language accessible to

everyone, not just the aristocracy who could read the Chinese hanja that were

used beforehand. As a result, the script is incredibly accessible, and has been

described as “the most perfect phonetic system devised” because the shape of

consonants denote the general shape of the reader’s mouth when pronouncing

them, and vowels are vertical or horizontal lines to easily distinguish them

from consonants. The Hangul alphabet has superb conveyance because it was

specifically designed to make the language easy for people of any standing to

understand. In my research, I will critique the fictional scripts on the basis

of how accessible they are for someone with no prior experience with the

language.

Analysis: Tengwar Elvish

In the Tengwar alphabet, vowels are indicated by diacritics

called tehtar, which appear above or

below their paired consonant. In the Quenya mode, vowels pair with the

consonants which precede them; in the Sindarin mode, vowels pair with the

consonants which follow them. When a vowel starts/ends a word or otherwise

stands alone, a special vowel holder character is used. This character is a

short or long vertical line, depending on which vowel appears. Long vowels

never pair; instead they always use a long holder.

The use of diacritical vowels in Tengwar allows for a single

character to cover a wide range of intonations with only minor changes.

Furthermore, a stand-alone or long vowel has its own character, while paired

vowels appear as one unit with their consonant. This places a visual emphasis

on the phonetic syllables, as each glyph carries a full syllable and its

pronunciation without extra notes or multiple marks. For example, take ‘Quenya’ in the comparison below. In Tengwar, the word appears as two characters with the

pronunciation explicitly noted by the type of diacritics used. The ‘Que’

syllable is pronounced as ‘kwe’, as indicated by the ‘kw’ tengwa and the ‘e’ tehtar,

and the ‘nya’ is obviously one syllable with a short ‘a’. By contrast, in

English the word is six characters, and pronunciation is ambiguous without any

accents or other notes. The ‘Qu’ could be read as a ‘kw’ or ‘k’ sound, and any

of the vowels could be short or long, giving any number of syllables. Using

diacritics to contain the verbal information of a character is a strong feature

of Tengwar.

Tengwar has an extensive character set, yet only a few basic

character shapes. Take, for example, the first Quenya tengwa in the second column, ‘parma’. With the bow

doubled, it becomes ‘umbar’; with a raised stem, ‘formen’; with a raised stem

and doubled bow, ‘ampa’; with a short stem and doubled bow, ‘malta’; with a

short stem, ‘vala’. In this way, only four basic shapes cover twenty four

phonetic sounds. A tilde or bar under a consonant doubles the sound of the

letter. Despite this simplicity, Tengwar has several rules that alter a

character’s form or usage:

1) When followed by a vowel, the letters ‘s’, ‘ss’, and ‘r’

are written with the tengwa ‘silme

nuquerna’, ‘esse nuquerna’ and ‘rómen’, respectively; otherwise these letters

are written with the tengwa ‘silme’,

‘esse’ and ‘óre’.

2) When a consonant precedes an ‘s’, it is written with a

small downward hook and the ‘s’ tengwa

is omitted.

These rules serve to make a word’s meaning more clear by

using a specific character for a specific purpose, much like English

capitalizes the letter ‘i’ to ‘I’ when used as a personal pronoun. The

characters of the Tengwar alphabet are not inherently complex, however their

implementation has features that allow simple adjustments to create complex

results.

Tengwar is an incredibly structural script, and should be

parsed as such. Identifying individual phonetic combinations is key, and the

diacritical vowels make this involved but simple. Take the sentence below.

The first word begins with a vowel holder for ‘e’, followed by a ‘Te’ pair and

an ‘n’. The second word has an ‘s’, a holder for ‘í’, and a ‘La’ pair.

Continuing in this manner, we can read the sentence as ‘Elen síla lumenn

omentielvo’, which is Elvish for ‘A star shines on the hour of our meeting’. It

is possible to parse this sentence without being explicitly told which mode of

Elvish it uses: the first word is paired as ‘E Le N’, not as ‘El En’, so it

must be Quenya mode because vowels pair with their preceding consonant. In this

regard, Tengwar has superb conveyance because the structure of the word itself

gives the reader information they may not have had to start.

Analysis: Circular Gallifreyan

Circular

Gallifreyan uses diacritical vowels somewhat like Tengwar, but pairs are always

made with the preceding consonant. Stand-alone vowels have no holder character,

instead ‘floating’ on the main circle of the word. When two vowels follow a

consonant, the first is paired and the second floating (e.g. ‘REAL’ = ‘Re A

L’). Pairs can be broken at the author’s discretion to elongate short words

(e.g. ‘THE’ = ‘T He’ or ‘T H E’). Doubled vowels are indicated by two circles

instead of one. Vowels appear as small circles relative to the main circle, and

no pronunciation is noted by the vowels. That is, both a short and long ‘e’

would appear as the same small circle on the line of the word. This usage of

only simple vowels is a weakness of Circular Gallifreyan; no accents or other

modifiers are represented, only the basic sound. However, using diacritics for

vowels in the first place is a strength shared with Tengwar. Pairing a

consonant with a vowel conveys phonetic or syllabic information that is not

present in the English translation.

Circular

Gallifreyan also uses only four basic shapes: a horseshoe, a circle inside the

word line, a semicircle, and a circle on the word line. Different characters

are formed by adding a number of lines or dots, allowing each base shape to

represent six individual phonetic sounds. Dots are contained

within the consonant shape, while lines can be written in several ways: they

can extend a small distance in-line from the consonant, connect with lines from

other consonants or words, or extend all the way to the opposite side of the

word. This is a purely aesthetic choice, and has no impact on the meaning of a

word or sentence.

The

characters used in Circular Gallifreyan are incredibly basic, and as such can

be written by the most inexperienced of hands, which is a great strength of the

language. Reading the script, however, can be much more difficult because the

symbols are so much alike and hard to differentiate without a table like this one.

Circular

Gallifreyan is, of course, a script built on circles. A word begins at the

bottom of a circle and reads letters anticlockwise, and a sentence begins at

the bottom of two concentric circles and reads words anticlockwise. In a manner

of speaking, a sentence is like a word made of other words. At first glance, a

sentence can seem a convoluted mass of circles, but the level of complexity can

be reduced dramatically by breaking it up into individual words before parsing.

For example, to analyze the sentence below, first see that the outer

two circles designate a sentence, and the individual circles within represent

four words. Note how the second version is much easier to parse as “Bow ties are cool.”

once the lines crossing multiple words are broken and the sentence circles

removed.

Analysis: Daedric

In

stark contrast to the other two languages, the Daedric script uses no

diacritical marks. Vowels are their own sigils, and there are no accents or

other modifiers. This could be read as a weakness because only raw letter

information is contained within the sigils, or as a strength because the simple

structure of the text makes transcription easy.

The

Daedric alphabet has very distinct sigils. Only a few sigils share a base

shape, however many sigils closely resemble their English counterparts. For

example, note how ‘Doht’, ‘Lyr’, ‘Meht’, and ‘Neht’ appear as calligraphic ‘D’,

‘L’, ‘M’, and ‘N’, respectively. Others appear as inversions or other

manipulations of English letters: ‘Payem’ is a backwards ‘P’, ‘Jeb’ is a

rotated ‘J’, and ‘Yoodt’ is an incomplete ‘U’. In a way, Daedric functions

rather like an ornate typeface for Latinate script and otherwise is structured

identically, reading left-to-right and top-to-bottom.

Daedric

is one of the easier fictional languages to parse because it is a direct

one-to-one transcription of English letters. There are no diacritical vowels or

phonetics to decode as in Tengwar, and no structures to break apart as in

Circular Gallifreyan. Text is written left-to-right and top-to-bottom, either in lines or in clusters; in the latter case, the first letter of each word is enlarged and can be colored to easily separate clusters.

On the other hand, the lack of such details can also

inhibit a reader’s understanding of the script because only the raw letter data

is presented. Daedric’s level of conveyance, therefore, is largely dependent on

what the script actually says. When pronunciation is key, Daedric affords no

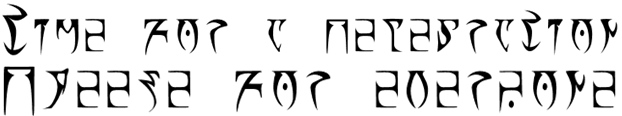

help; when only written transcription is required, Daedric has superb conveyance. The text below is easy enough to transcribe,

reading “Time for a celebration. Cheese for everyone!”, which is one of the

more memorable quotes from TES4: Oblivion.

Daedric has a very ‘Other’ feel to the sigils, which is entirely intentional by

its creators. If the letters look arcane and occult, it’s because they are not

meant for mortal eyes.

|

| The thrice sealed house withstands the storm |

Overall Analysis

Tengwar

is an incredibly well-built language, and is used extensively in Tolkien’s

books to add depth to his worldbuilding. As a script, it functions much like

Tibetan and other Brahmi-derived languages, with diacritical vowels and small

modifiers to change between consonants. Tengwar’s primary strength is in its

system of creating numerous phonetic combinations with only a small set of base

shapes, and its main weakness is in the number of rules that a writer must keep

track of to accurately say the right thing. The dual modes present an added

layer of complexity which is great for mythos, but a nightmare for a practical

application of the script. All in all, Tengwar is a complex language based on a

large number of simple principles.

Circular Gallifreyan is born

from the Time Lords’ understanding of the cyclical nature of time. Its script

consists entirely of circles and lines, and sentences are circles within

circles. For anyone writing the script, many aesthetic decisions are entirely

up to the author’s discretion; for anyone reading the script, it is hard to

understand without first undoing much of the work that went into structuring

the sentence. Circular Gallifreyan is simultaneously simplistic in its

character system and complex in its sentence structure. The varying levels of

detail make the script easily legible in short form yet exceedingly arcane in

long form.

Daedric

script was created to be a direct one-to-one transcription to and from English,

and so lacks many of the features that make the other two languages so

unique. What Daedric does offer, however, is a look into how we view the

letters themselves, and how the general ‘feel’ of a script can give meaning and

mythos to a story. The rough characters crop up periodically in the Elder Scrolls video games, and whenever

they do, it means the occult is soon to follow. As a script,

Daedric provides a way to write English in a completely new way without the

need to learn new structural rules, only a character set.

Recommendations for Writers

It is

hard to say what makes a ‘good’ language and what makes a ‘bad’ one. We can,

however, observe what features some popular fictional languages employ and see

what impact they have on the script and how readers understand it. Diacritics

can be a great tool for cleaning up a language, such as making vowels purely

diacritical, but if you only want to make a written language, then leaving them

out is perfectly fine. As long as you have well-defined rules for their usage,

anything goes for what marks you put on your characters. Multiple characters

that share a common base form can give you a lot of flexibility and let a small

number of shapes cover a wide range of letters. On the other hand, perhaps you

want to make a script that has many distinct shapes, in which case you can come

up with your own glyphs or modify letters from real world scripts to suit your

needs. In any event, however, your language must be able to convey its meaning

to the reader. If no one can understand what your script says, then what useful

purpose does it serve? Employ as many or as few of these devices as you wish,

just remember that ‘more complex’ does not necessarily mean ‘sophisticated’,

and ‘simple’ doesn’t mean ‘crude’. As long as your language can make its

meaning clear through whatever features you decide to use, then any language

can be a great one.

References

“A Guide to the Gallifreyan Alphabet.” Sherman, Loren. n.p., n.d. Web. 2 April2014.

"Biangbiang noodles." Wikipedia. MediaWiki, 1 March 2014. Web. 2 April 2014.

"Biangbiang noodles." Wikipedia. MediaWiki, 1 March 2014. Web. 2 April 2014.

“CircularGallifreyan.” Timeturners. Wikidot,n.d. Web. 2 April 2014.

"Daedric Alphabet." Ager, Simon. Omniglot. Kualo, 2014. Web. 2 April 2014.

"Daedric Alphabet." Ager, Simon. Omniglot. Kualo, 2014. Web. 2 April 2014.